Progress is being made in the commercialization of 3D printed pharmaceuticals

Researchers have used volumetric 3D printing to fabricate drug-loaded tablets within a matter of seconds, reportedly for the first time.

Hailing from University College London (UCL), the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC), the MERLN Institute for Technology-Inspired Regenerative Medicine, and pharmaceutical 3D printing specialist FabRx, the researchers successfully produced paracetamol-loaded tablets within 17 seconds, which is significantly faster than current methods used to print pharmaceuticals within research and some clinical settings.

The team believes its work demonstrates the suitability of volumetric 3D printing for producing drug products using additive manufacturing, and could potentially enable rapid, on-demand production of medicines and medical devices in the future.

Commercializing 3D printed drugs

3D printing offers a number of advantages for clinical pharmaceutical drug development over traditional methods. Not only does the technology enable medicines to be personalized to the needs of individual patients, but it also has the potential to expedite drug delivery timelines and provide on-demand medication to those in hospitals, pharmacies, and hard-to-reach areas.

While these benefits have been widely demonstrated on a research level in recent years, the clinical potential of the technology is yet to be realized. FabRx is one of the pioneers of this field, having developed its own GMP-ready (good manufacturing practice) pharmaceutical 3D printer, the M3DIMAKER, which is currently available for research purposes.

In the past, FabRx has leveraged its pharmaceutical 3D printing capabilities to produce personalized medicine for children with the rare metabolic disorder maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) and to fabricate tablets with braille and moon patterns on the surface to aid medicine taking for the visually impaired.

More recently, FabRx, UCL and USC worked together to 3D print novel drug-loaded punctal plugs designed to treat dry eye disorder, and a 3D printed device capable of removing pharmaceutical drugs from water supplies.

Aside from FabRx, there are several other companies taking strides to commercialize the technology. In fact, Aprecia has already realized the commercial potential of 3D printed pharmaceuticals, having received FDA approval for its Spritam epilepsy medication back in 2015. Since then, the firm has partnered with non-profit R&D firm Battelle to increase its manufacturing output and advance its ZipDose 3D printing system from clinical supply to commercial sale.

Meanwhile, global pharmaceutical firm Merck has entered into a joint project with EOS Group company AMCM to develop and produce 3D printed tablets, initially for clinical trials and then later for commercial manufacturing.

Volumetric 3D printing tablets

While progress is being made in the commercialization of 3D printed pharmaceuticals, challenges still remain to fully translate the technology from the lab to clinics on the ground. In particular, current 3D printing technologies are not yet capable of scaling up to produce the required billions of tablets per year for commercial manufacturing, due to throughput challenges.

In their latest study, the researchers sought to overcome this particular obstacle by leveraging volumetric 3D printing, which offers rapid printing speeds. Unlike layer-by-layer vat photopolymerization techniques, volumetric printing cures an entire 3D geometry simultaneously within a vat of resin using light, to produce whole objects in a single step.

The team claims this is the first time volumetric printing has been used to produce drug-loaded tablets, and significantly shortened the time needed to produce the tablets to a matter of seconds. The researchers tested six different resin formulations, each containing paracetamol, a cross-linking monomer and a photoinitiator, and were able to tune the printed tablets’ drug release rates to the desired speed.

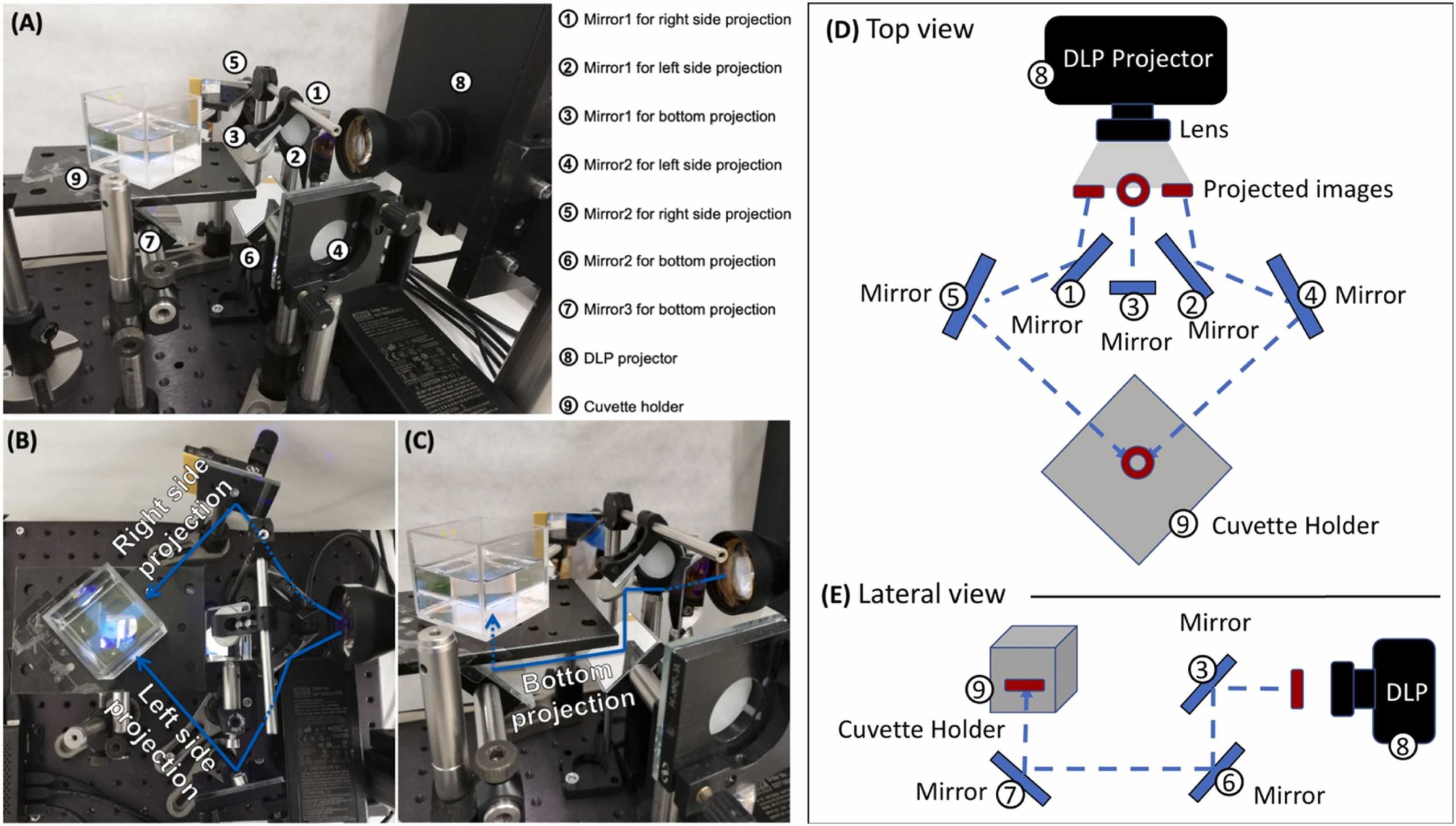

The volumetric 3D printer used for the study is from FabRx, and is based on a digital light projector made up of a digital mirror device, a UV light source, and UV optical lenses. The researchers 3D printed paracetamol-loaded tablets, or “Printlets” as FabRx calls them, in torus shapes 11mm in diameter and 4mm in height, with a 3mm diameter hole.

The team chose to print the tablets in torus shapes as the geometry affords a greater surface area to volume ratio compared to a disc, and therefore accelerates the rate of drug release. Eight Printlets were printed consecutively for each resin formulation in just seven to 17 seconds, before undergoing a post-curing process where they were washed with isopropanol and placed in an oven for one hour at 20°C.

According to the researchers, the method is the fastest way of producing personalized tablets via 3D printing that has been demonstrated so far, and therefore confirms the suitability of volumetric 3D printing for producing medicines at rapid speeds.

Going forwards, the team will look to develop a system to automatically optimize the printing parameters for different photosensitive resins, which could involve the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to accelerate the development process and predict the printing performance of different formulations. This could also enable the fabrication of more complex geometries to extend the application of volumetric 3D printing to other drug-loaded medical devices.

While further research is needed to investigate the biocompatibility of the photosensitive resins used in the study, the team believes that volumetric 3D printing could “enable a virtuous cycle of personalized medicine and provide significant improvement in health outcomes.”

Further information on the study can be found in the paper titled: “Volumetric 3D printing for rapid production of medicines,” published in the Additive Manufacturing journal. The study is co-authored by L. Rodriguez-Pombo, X. Xu, A. Seijo-Rabina, J. Ong, C. Alvarez-Lorenzo, C. Rial, D. Nieto, S. Gaisford, A. Basit, and A. Goyanes.

Tags: 3D Printing New Drug Trends New Technology